Oliver R. Hoor is a Tax Partner (Head of Transfer Pricing and the German Desk) with ATOZ Tax Advisers (Taxand Luxembourg).

The 2019 Luxembourg Tax Reform: Analysing the Impact on Private Equity Investments

by Oliver Hoor, Partner, ATOZ

- Introduction

- Typical Private Equity Investment Structures

- Interest Limitation Rules

- General Anti-Abuse Rule (GAAR)

- Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) Rules

- Anti-hybrid Mismatch Rules

- Exit Tax Rules

- Amendment of the Luxembourg Roll-over Relief

- Amendment of the Permanent Establishment Definition

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, Luxembourg has emerged to the location of choice for the structuring of private equity investments in and through Europe. The attractiveness of Luxembourg is linked to a host of factors, which have made it an essential part of the global financial architecture.

These factors include its flexible and diverse legal, regulatory and tax framework, investor and lender familiarity with the jurisdiction, the availability of qualified, multilingual workforce, the existence of a deep pool of experienced advisers and service providers, a large tax treaty network, an investor-friendly business and legal environment, and political stability, to name a few reasons. Moreover, Luxembourg is a founder member of and sits at the heart of the European Union, one of the largest sources of capital and investment opportunities globally.

The Luxembourg Parliament has now adopted the 2019 tax reform implementing the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (“ATAD”) and other anti-BEPS-related measures into Luxembourg tax law. More precisely, the 2019 tax reform includes tax law changes in the following areas:

- Interest limitation rules;

- General anti-abuse rule (GAAR);

- Controlled foreign companies (CFCs);

- Hybrid mismatch rules;

- Amendment of the exit tax rules;

- Amendment of the roll-over relief; and

- Amendment of the permanent establishment definition.

This article provides a clear and concise overview of the different tax measures and analyses their impact on typical private equity investments.

2. Typical Private Equity Investment Structures

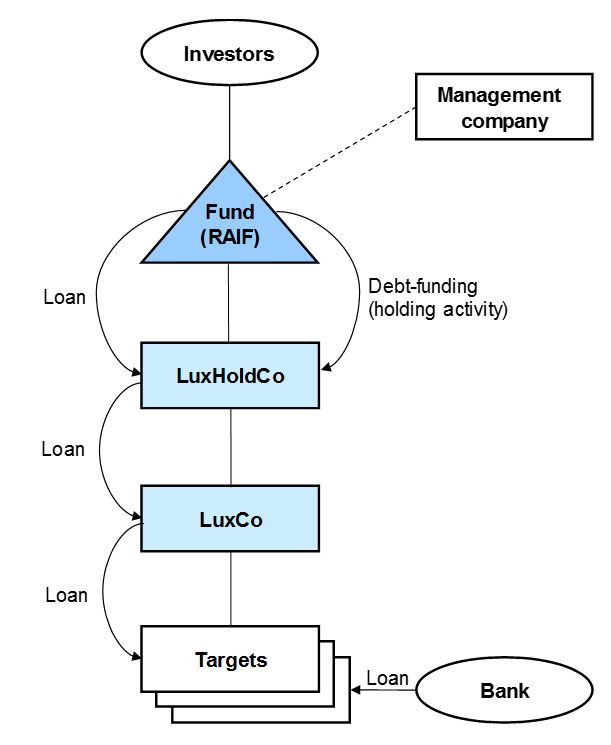

Private equity investments are typically made via a Luxembourg or foreign fund vehicle (the “Fund”) and Luxembourg companies which acquire businesses. The Luxembourg investment platform of the fund may, for example, consist of a Luxembourg master holding company (“LuxHoldCo”) and separate Luxembourg companies (“LuxCo”) for the different investments.

The target companies are generally financed by a mixture of equity and debt. Where debt funding is provided to subsidiaries, Luxembourg companies will generally finance such receivables by debt instruments (for example, shareholder loans). When investments are held via two or more Luxembourg companies, the funds granted in the form of debt to the target companies may be routed via one or more Luxembourg companies.

Additional funding may be obtained from external sources (for example, banks) by the operational companies.

The following chart depicts a typical private equity fund structure:

3. Interest Limitation Rules

Since 1 January 2019, Article 168bis of the Luxembourg Income Tax Law limits the deductibility of “exceeding borrowing costs” generally to a maximum of 30% of the corporate taxpayers’ earnings[1] before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). The scope of the interest limitation rules encompasses all interest-bearing debts irrespective of whether the debt financing is obtained from a related party or a third party. However, exceeding borrowing costs up to an amount of EUR 3m may be deducted without any limitation (that is a safe harbour provision).

“Exceeding borrowing costs” correspond to the amount by which the deductible “borrowing costs” of a taxpayer exceed the amount of taxable “interest revenues and other economically equivalent taxable revenues”. Borrowing costs within the meaning of this provision include interest expenses on all forms of debt, other costs economically equivalent to interest and expenses incurred in connection with the raising of finance.

As far as interest income and other economically equivalent taxable revenues are concerned, neither ATAD nor Luxembourg tax law provides for a clear definition of what is to be considered as “revenues which are economically equivalent to interest”. However, given that borrowing costs and interest income should be mirroring concepts, the latter should be interpreted in accordance with the broad definition of borrowing costs.

Corporate taxpayers who can demonstrate that the ratio of their equity over their total assets is equal to or higher than the equivalent ratio of the group can fully deduct their exceeding borrowing costs (that is the so-called “escape clause” that should protect multinational groups that are highly leveraged).

Moreover, according to a recent announcement of the Luxembourg Government, the optional provision under ATAD according to which EBITDA and exceeding borrowing costs can be determined at the level of the consolidated group (i.e. when several companies form a fiscal unity) will be introduced within the upcoming six months with retroactive effect as from 1 January 2019.

- Entities excluded from the scope of the rule

The interest limitation rules explicitly exclude financial undertakings and standalone entities from its scope.

Financial undertakings are the ones regulated by the EU Directives and Regulations and include among others financial institutions, insurance and reinsurance companies, undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (“UCITS”), alternative investment funds (“AIF”) as well as securitisation undertakings that are subject to EU Regulation 2017/2402.

Standalone entities are entities that (i) are not part of a consolidated group for financial accounting purposes and (ii) have no associated enterprise or permanent establishment. Thus, in order for a Luxembourg company to benefit from the standalone entity exception, it is necessary that none of the associated enterprises has directly or indirectly a participation of 25% or more.[2] It is interesting to note that the definition of associated enterprise for the purpose of the newly introduced provisions is defined very broadly including individuals, companies and transparent entities such as partnerships.

- Loans excluded from the scope of the rule

According to Article 168 of the ITL, loans concluded before 17 June 2016 are excluded from the restrictions on interest deductibility. However, this grandfathering rule does not apply to any subsequent modification of such loans. Therefore, when the nominal amount of a loan granted before 17 June 2016 is increased after this date, the interest in relation to the increased amount would be subject to the interest limitation rules. Likewise, when the interest rate is increased after 17 June 2016, only the original interest rate would benefit from the grandfathering rule.

Nevertheless, when companies are financed by a loan facility that determines a maximum loan amount and an interest rate, the entire loan amount should be excluded from the scope of the interest limitation rules irrespective of when the drawdowns have been made.[3]

Moreover, loans used to fund long-term public infrastructure projects are excluded from the scope of the interest deduction limitation rule.

- Carry forward mechanisms

The interest deduction limitation rule also provides for a carry forward mechanism in regard to both non-deductible exceeding borrowing costs and unused interest capacity.

Non-deductible exceeding borrowing costs are interest expenses which cannot be deducted because they exceed the limits set in article 168bis of the LITL. Such exceeding borrowing costs may be carried forward without time limitation and deducted in subsequent tax years.

Unused interest capacity arises in a situation in which the exceeding borrowing costs of the corporate taxpayer are lower than 30% of the EBITDA to the extent they exceed EUR 3m. These amounts can be carried forward for a period of 5 tax years.

In case of corporate reorganisations that fall within the scope of article 170 (2) of the LITL (for example, mergers), exceeding borrowing costs and unused interest capacity will be continued at the level of the remaining entity.

Analysing the Impact on Private Equity Investments

When analysing the impact of the interest limitation rules on private equity funds, it is crucial to distinguish the different activities performed by the Luxembourg companies involved.

- Financing activities

When Luxembourg companies perform financing activities or on-lend funds, the receivables owed by other group companies are generally financed by debt instruments (for example, LuxCo grants a loan to its subsidiary that is financed by a loan from LuxHoldCo).[4] In this regard, the Luxembourg company has to realize an arm’s length remuneration which should be reflected in the interest rates applied. In other words, Luxembourg companies should realize more interest income than interest expenses. It follows that in case of financing activities the interest limitation rules should not apply in the absence of exceeding borrowing costs.

- Holding activities

With regard to holding activities, the potential impact of the interest limitation rules depends on how the participations are financed. Here, the investors have the choice between a range of equity and debt instruments.

In many cases, Luxembourg companies will not incur deductible interest expenses in relation to the holding of participations. This might be because of the instrument used (not creating any tax-deductible expenses) or the fact that interest expenses incurred in direct economic relationship to tax exempt income are not deductible for tax purposes.[5] Nevertheless, the interest limitation rules only apply in case of tax-deductible interest expenses.

When a Luxembourg company finances a participation by a debt instrument that bears fixed interest, the interest expenses incurred should be deductible to the extent the interest expenses exceed tax exempt dividend income in a given year. In these circumstances, the amount of deductible interest expenses should be limited to EUR 3m (i.e. the safe harbour).[6]

- Other activities

When Luxembourg companies realize other financial income such as capital gains in regard to loan receivables or income from derivatives, the new rules should limit the deductibility of interest expenses if it is not possible to rely on the EUR 3m safe harbour.

Hence, whenever it is expected that a Luxembourg company may realize significant amounts of income of these categories, it is crucial to consider potential tax implications beforehand.

4. General Anti-Abuse Rule (GAAR)

The Luxembourg abuse of law concept as defined in §6 of the Tax Adaptation Law (“Steueranpassungsgesetz”) has been replaced by a new GAAR that keeps the key aspects of the previous abuse of law concept (according to which “the tax law cannot be circumvented by an abuse of forms and legal constructions”) whilst introducing the concepts of the GAAR provided under ATAD.

According to the new provision non-genuine arrangements or a series of non-genuine arrangements put into place for the main purpose or one of the main purposes of obtaining a tax advantage that defeats the object or purpose of the applicable tax law shall be disregarded. Arrangements are considered as non-genuine to the extent that they are not put into place for valid commercial reasons which reflect economic reality.

When the Luxembourg tax authorities can evidence an abuse in accordance with the new GAAR, the amount of taxes will be determined based on the legal route that is considered as the genuine route (i.e. based on the legal route which would have been put into place for valid commercial reasons which reflect economic reality).

In terms of scope, the new GAAR is broader than the GAAR provided under ATAD. While the latter only applies to corporate income taxes and taxpayers, the Luxembourg GAAR applies to all taxpayers and is not limited to corporate income tax.

However, in practice the scope of the new GAAR should be limited to clearly abusive situations and, in an EU context, to wholly artificial arrangements considering relevant jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”).

Analysing the Impact on Private Equity Investments

The GAAR is generally targeted at abusive transactions that are tax driven. However, private equity investments are frequently made for legitimate commercial reasons such as the generation of ongoing income and the realization of capital gains upon a future exit. Moreover, the CJEU confirmed on numerous occasions the right of taxpayers to arrange their affairs in a way that results in the lowest tax liability.

In light of the above, when private equity investments are properly managed (good corporate governance, proper legal documentation, appropriate substance in Luxembourg, etc.), Luxembourg companies should be out of reach of the new GAAR.

5. Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) Rules

Companies that are part of the same group are generally taxed separately as they are separate legal entities. When a Luxembourg parent company has a subsidiary, the profits of the subsidiary are only taxable at the level of the parent company once the profits are distributed. Depending on the residence state and tax treatment of the subsidiary, dividend income may either be tax exempt (in full or in part) or taxable with a right to credit a potential withholding tax levied at source.[7] Thus, if a foreign subsidiary is located in a low-tax jurisdiction, the taxation of the profits of such entity may be deferred through the timing of the distribution.

In this regard, ATAD requires EU Member States to implement CFC rules that re-attribute the income of a low-taxed controlled company (or permanent establishment) to its parent company even though such income has not been distributed. However, EU Member States have a certain leeway when it comes to the implementation of the CFC rules. More precisely, legislators may choose between two alternatives regarding the fundamental scope of the CFC rules (i.e. the passive income option vs. the non-genuine arrangement option) and have the option to exclude certain CFCs.

- Definition of CFCs

According to Article 164ter of the LITL, a CFC is an entity or a permanent establishment of which the profits are either not subject to tax or exempt from tax in Luxembourg provided that the following two cumulative conditions are met:

(i) In the case of an entity, the Luxembourg corporate taxpayer by itself, or together with its associated enterprises

- a) holds a direct or indirect participation of more than 50 percent of the voting rights; or

- b) owns directly or indirectly more than 50 percent of capital; or

- c) is entitled to receive more than 50 percent of the profits of the entity (the “control criterion”)

and

(ii) the actual corporate tax paid by the entity or permanent establishment is lower than the difference between (i) the corporate tax that would have been charged in Luxembourg and (ii) the actual corporate tax paid on its profits by the entity or permanent establishment (the “low tax criterion”).

In other words, the actual tax paid is less than 50% of the tax that would have been due in Luxembourg. Given the currently applicable corporate income tax rate of 18% (this rate should be reduced to 17% as from 2019 based on recent announcement of the Luxembourg Government), the CFC rule will only apply if the taxation of the profits at the level of the entity or permanent establishment is lower than 9% (8.5% as from 2019) on a comparable taxable basis.[8]

When assessing the actual tax paid by the entity or permanent establishment only taxes that are comparable to the Luxembourg corporate income tax are to be considered.[9]

- Exceptions

The Luxembourg legislator adopted the options provided under ATAD according to which the following entities or permanent establishments are excluded from the scope of the CFC rules:

- An entity or permanent establishment with accounting profits of no more than EUR 750.000; or

- An entity or permanent establishment of which the accounting profits amount to no more than 10% of its operating costs for the tax period.[10]

- Determination and tax treatment of CFC income

CFC income is subject to corporate income tax at a rate of currently 18%.[11] However, a specific deduction has been included in the municipal business tax law to exclude CFC income from the municipal business tax base.[12]

With regard to the fundamental scope of the CFC rules, Luxembourg has opted for the non-genuine arrangement concept. Accordingly, a Luxembourg corporate taxpayer will be taxed on the non-distributed income of an entity or permanent establishment which qualifies as a CFC provided that the non-distributed income arises from non-genuine arrangements which have been put in place for the essential purpose of obtaining a tax advantage.

In practice, this means that the profits of a CFC will only need to be included in the tax base of a Luxembourg corporate taxpayer if, and to the extent that, the activities of the CFC that generate these profits are managed by the Luxembourg taxpayer (i.e. when the significant people functions in relation to the assets owned and the risks assumed by the CFC are performed by the Luxembourg corporate taxpayer). Conversely, when a Luxembourg parent company does not carry out any significant people functions in relation to the activities of the CFC, no CFC income is to be included in the corporate income tax base of the Luxembourg parent company.[13]

When a Luxembourg corporate taxpayer is involved in the management of the activities performed by the CFC, the CFC income to be included by the Luxembourg corporate taxpayer should be limited to amounts generated through assets and risks which are linked to significant people functions carried out by the Luxembourg taxpayer. Here, the attribution of CFC income shall be calculated in accordance with the arm’s length principle[14].[15]

The income to be included in the tax base shall further be computed in proportion to the taxpayer’s participation in the CFC and is included in the tax period of the Luxembourg corporate taxpayer in which the tax year of the CFC ends.

Last but not least, Article 164ter of the LITL provides for rules that aim to avoid the double taxation of CFC income (for example, when CFC income is distributed or a participation in a CFC is sold).

Analysing the Impact on Private Equity Investments

Private equity investments are generally made in high-tax jurisdictions. Here, the CFC rules do not apply in the absence of low-taxed subsidiaries.

When investments are made into a group of companies that has a subsidiary in a low-tax jurisdiction, the Luxembourg CFC rules should only apply if and to the extent the Luxembourg company performs the significant people functions in regard to the activities performed by the CFC. However, this is a scenario that should hardly ever occur in practice.

6. Anti-hybrid Mismatch Rules

The tax reform law further introduced a new article 168ter LITL which implements the generic anti-hybrid mismatch provisions included in ATAD. The new provision aims to eliminate – in an EU context only – the double non-taxation created through the use of certain hybrid instruments or entities.

The law does not implement though the amendments introduced subsequently by ATAD 2 to ATAD which have replaced the anti-hybrid mismatch rules provided under ATAD and extended their scope of application to hybrid mismatches involving third countries. ATAD 2 provides for specific and targeted rules which have to be implemented by 1 January 2020. As such, the anti-hybrid mismatch rule provided in ATAD did not have to be implemented in 2019.

The objective of the measures against hybrid mismatches is to eliminate double non-taxation outcomes created by the use of certain hybrid instruments or entities. In general, a hybrid mismatch exists where a financial instrument or an entity is treated differently for tax purposes in two different jurisdictions. The effect of such mismatches may be a double deduction (i.e. a deduction in two EU Member States) or a deduction of the payment in one state without the inclusion of the payment in the other state.

However, in an EU context, hybrid mismatches have already been tackled through several measures such as the amendment of the Parent/Subsidiary-Directive (i.e. dividends should only benefit from the participation exemption regime if the payment is not deductible at the level of the paying subsidiary). Therefore, the hybrid mismatch rule included in the new article 168ter LITL should have a limited scope of application. However, given the generic wording of the anti-hybrid mismatch rule, the latter may create significant legal uncertainty in 2019 even if the existence of a hybrid situation is not at all linked to tax motives.

- Rule applicable to double deduction

To the extent that a hybrid mismatch results in a double deduction, the deduction shall be given only in the EU Member States in which the payment has its source. Thus, in case Luxembourg is the investor state and the payment has been deducted in the source state, Luxembourg will deny the deduction. However, this situation should hardly ever occur in practice.

- Rule applicable in case of deductions without inclusion

When a hybrid mismatch results in a deduction without inclusion, the deduction shall be denied in the payer jurisdiction. Therefore, if Luxembourg is the source state and the income is not taxed in the recipient state, the deduction of the payment will be denied in Luxembourg.

In practice, income that is treated as dividend income at investor level should, in accordance with the current version of the EU Parent/Subsidiary Directive, only benefit from a tax exemption if the payment was not deductible at the level of the Luxembourg company making the payment. Therefore, these situations should generally not occur in an EU context.

- How to benefit from a tax deduction in practice

In order to be able to deduct a payment in Luxembourg, the Luxembourg corporate taxpayer will have to demonstrate that no hybrid mismatch situation exists. Here, the taxpayer will have to provide evidence to the Luxembourg tax authorities that either (i) the payment is not deductible in the other Member State which is the source state or (ii) the related income is taxable in the other Member State.

This evidence is primarily provided through the statements made in the corporate tax returns. Nonetheless, in practice the Luxembourg tax authorities may ask for further information and proof in this respect.

Analysing the Impact on Private Equity Investments

The scope of the new rules is limited to hybrid mismatch situations in an EU context. However, within the EU, hybrid mismatches have already been tackled by several initiatives (for example, the anti-hybrid mismatch rule included in the Parent/Subsidiary Directive) and double non-taxation/deduction outcomes should be fairly uncommon in practice. Therefore, the 2019 anti-hybrid mismatch rules should have a limited impact on private equity investments.

Given their generic nature, however, the anti-hybrid mismatch rules as they stand may still have the potential to create significant legal uncertainty. For example, in situations when a fund vehicle is treated as opaque in the EU Member State(s) in which the investors are resident, whereas the vehicle is treated as fiscally transparent from a Luxembourg tax perspective. In these circumstances, one may construe that the fund vehicle is a hybrid entity.

Considering the implementation of the comprehensive anti-hybrid mismatch rules provided under ATAD 2 in 2020 (applying in an EU context and in situations involving third states), it would be wise for taxpayers to anticipate the potential impact on investments. One particular concern in this respect relates to private equity investments of US investors given the particularities of US tax law.

7. Exit Tax Rules

The tax reform further provides for tax law changes in regard to exit taxation that will become applicable as from 1 January 2020. These measures should discourage taxpayers from moving their tax residence and/or assets to low-tax jurisdictions. However, to a large extent, Luxembourg tax law provided already for exit tax rules.

- Rule applicable to transfers to Luxembourg

As far as transfers to Luxembourg are concerned, a new paragraph has been added to article 35 of the LITL providing that in case of a transfer of assets, tax residence or business carried on by a permanent establishment to Luxembourg, Luxembourg will follow the value considered by the other jurisdiction as the starting value of the assets for tax purposes, unless this does not reflect the market value.

The aim of this linking rule is to achieve coherence between the valuation of assets in the country of origin and the valuation of assets in the country of destination. While ATAD limits the scope of application of this provision to transfers between two EU Member States, the new provision added to article 35 LITL covers transfers from any other country to Luxembourg.

- Rule applicable to contributions to Luxembourg

The same valuation principles will also apply to contributions of assets (“supplement d’apport”) within the meaning of article 43 LITL. Thus, when assets are contributed to a Luxembourg company, the value considered in the jurisdiction of the contributing company or permanent establishment will be considered as value of the assets for tax purposes, unless this does not reflect the market value.

- Rule applicable to transfers out of Luxembourg

As far as transfers out of Luxembourg are concerned, the tax reform law provides that a taxpayer shall be subject to tax at an amount equal to the market value of the transferred assets at the time of the exit less their value for tax purposes in case of:

– A transfer of assets from the Luxembourg head office to a permanent establishment located in another country, but only to the extent that Luxembourg loses the right to tax the transferred assets;

– A transfer of assets from a Luxembourg permanent establishment to the head office or to another permanent establishment located in another country, but only to the extent that Luxembourg loses the right to tax the transferred assets;

– A transfer of tax residence to another country except for those assets which remain connected with a Luxembourg permanent establishment; and

– A transfer of the business carried on through a Luxembourg permanent establishment to another country but only to the extent that Luxembourg loses the right to tax the transferred assets.

In case of transfers within the European Economic Area (EEA), the Luxembourg taxpayer may request to defer the payment of exit tax by paying in equal instalments over 5 years. § 127 of the General Tax law (“Abgabenordnung”) is amended accordingly.

Analysing the Impact on Private Equity Investments

Private equity investments should generally not involve any of the aforementioned transactions. It follows that the amendment of the exit tax rules and the introduction of linking rules with regard to migrations and contributions should have a limited impact in this respect.

8. Amendment of the Luxembourg Roll-over Relief

Article 22bis of the LITL provides for exceptions to the general rule that Luxembourg taxpayers have to realize the latent capital gains linked to assets that are exchanged for other assets. As from 2019, the provision applicable to a specific category of exchange operations involving the conversion of a loan or other debt instruments into shares of the borrower has been abolished.

Hence, the conversion of debt instruments into shares of the borrowers will no longer be possible in a tax neutral manner. Instead, the conversion will be treated as a sale of the debt instrument followed by a subsequent acquisition of shares. Accordingly, any latent gain on the debt instrument will become fully taxable upon the conversion.

The amendment of article 22bis of the LITL follows the State Aid investigations of the EU Commission in the Engie case. However, while the aim of this amendment is to ensure that double non-taxation outcomes can no longer arise from this provision, it would have been wise to implement more targeted measures to avoid collateral damage.

Analysing the Impact on Private Equity Investments

As a matter of principle, whenever a debt instrument should be contributed by a Luxembourg company, consideration should be given to the question as to whether the fair market value of the receivable exceeds its book value. Where the amendment of the roll-over relief would result in adverse tax consequences, alternative restructuring options should be explored.

9. Amendment of the Permanent Establishment Definition

As a last measure, the definition of permanent establishment under Luxembourg tax law (§ 16 of the Tax Adaptation Law) has been amended. Under the amended permanent establishment definition, the criteria to be considered in order to assess whether a Luxembourg taxpayer has a permanent establishment in a country with which Luxembourg has concluded a tax treaty are the criteria defined in the tax treaty itself. In order words, the permanent establishment definition included in the tax treaty will be relevant.

Furthermore, unless there is a clear provision in the relevant tax treaty which is opposed to this approach, a Luxembourg taxpayer will be considered as performing all or part of its activity through a permanent establishment in the other contracting state only if the activity performed, viewed in isolation, is an independent activity which represents a participation in the general economic life in that contracting state. However, tax treaties concluded by Luxembourg generally include the permanent establishment definition provided in Article 5 of the OECD Model Convention that does not entail such requirement. Thus, the amendment of the Luxembourg PE definition should have no material impact in practice.

Finally, the Luxembourg tax authorities may request from the taxpayer a certificate issued by the other contracting state according to which the foreign authorities recognize the existence of the foreign permanent establishment.[16] Such certificate is, in particular, to produce when Luxembourg adopted the exemption method in a tax treaty and the other contracting state interprets the rules of the tax treaty in a way that excludes or limits its taxing rights. This is to avoid hybrid branch situations that are recognized in Luxembourg but disregarded in the host state of the permanent establishment.

Analysing the Impact on Private Equity Investments

Luxembourg companies involved in private equity investments do generally not operate through foreign permanent establishments. Therefore, the amendment of the permanent establishment definition should have no impact on private equity investments.

10. Conclusion

The 2019 tax reform introduces a number of new anti-avoidance rules into Luxembourg tax law. With regard to private equity investments, the interest limitation rules have to be in the focus of each and every tax analysis, whereas the other tax measures should in many cases have a limited effect. Nevertheless, the impact of the tax reform on a particular investment structure has to be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Anticipating the next tax reform in 2020, taxpayers should analyse whether the adoption of the comprehensive anti-hybrid mismatch rules provided under ATAD 2 may have an impact on investments and implement structure alignments where necessary.

Ultimately, the attractiveness of Luxembourg as a prime location for the structuring of private equity investments should not be undermined by the current tax developments. To the contrary, Luxembourg offers an ideal framework for private equity investments in the post-BEPS era.

[1] Tax exempt income such as dividends benefiting from the Luxembourg participation exemption regime are to be excluded when determining the EBITDA.

[2] In this regard, participation means a participation in terms of voting rights or capital ownership of 25% or more or the entitlement to receive 25% or more of the profits of that entity.

[3] This should remain valid as long as the conditions of the loan facility are not amended after 17 June 2016.

[4] When a Luxembourg company bears the risks in relation to the granting of loans (in particular, the credit risk), it will be considered as a finance company from a Luxembourg transfer pricing perspective and required to realize an arm’s length finance margin. In contrast, when a Luxembourg company merely on-lends funds without bearing any risks in relation to the on-lending of funds, it should be considered as a financial intermediary that needs to realize an arm’s length remuneration for the services rendered. The arm’s length remuneration for financial intermediation should be significantly lower than that of a Luxembourg finance company.

[5] Article 166 (5) No. 1 of the LITL.

[6] Should the Luxembourg company perform financing activities and realize a finance margin, the amount of deductible interest expenses should be limited to EUR 3m plus the amount of the finance margin.

[7] Article 97 (1) No. 1 of the Luxembourg Income Tax Law (“LITL”) in connection with Article 166 (1) (Luxembourg participation exemption regime), Article 115 No. 15 (50% tax exemption for dividends received from certain subsidiaries when the conditions of the participation exemption regime are not med) or Article 134bis (tax credit) of the LITL.

[8] Article 164ter (1) of the LITL.

[9] Article 164ter (1) of the LITL.

[10] Article 164ter (1) of the LITL.

[11] According to an announcement of the Luxembourg government, the corporate income tax rate should be decreased to 17% with retroactive effect as from 1 January 2019.

[12] Section 9 (3a) of the Luxembourg municipal business tax law.

[13] Article 164ter (4) No. 1 of the LITL.

[14] The arm’s length principle is formally specified in Articles 56 and 56bis of the LITL.

[15] Article 164ter (4) No. 1 of the LITL.

[16] This certificate should mainly evidence that the permanent establishment is recognized in the other contracting state. As there is generally no subject to tax requirement in tax treaties concluded by Luxembourg, the tax treatment of the income derived through the permanent establishment in the host state thereof should be irrelevant for the tax treatment in Luxembourg.